My father, Michael, was born in Co. Tyrone in 1941 and died in Dublin, which had been his home for many years, in 2006. He was an enthusiastic amateur scholar of the Irish language and having learned it in secondary school and beyond became a fluent speaker. This essay was written by him sometime in the 1990s. I am unsure whether it was ever published in any of the publications he occasionally submitted his work to. It is also unclear to me that I have the whole manuscript as it seems there might be more of a preamble. However, as presented it should still make sense to the reader. Apologies if there are any typos as my dad's handwriting could sometimes be a tad indecipherable. I haven't included the meaning of the Irish words from which the English dialectal words are derived but in most instances they're the same or similar. There were several thousand native speakers of the language in the county according to the 1911 Census. Some of these would ahve been born and bred in Tyrone while others were migrants from the Donegal Gaeltachtaí. As the century progressed the number of native Tyrone speakers dwindled. Nowadays the Irish language in the county has undergone a renaissance with many students being educated through it and many adults taking up lessons.

Many words used by local people in everyday speech are not to be found in the standard English dictionaries. These words have their origin on the one hand in the native Irish language, and on the other hand in the language of the settlers who came from Scotland and England in Plantation times. The words which I have listed below are some of the last local remnants of a tongue which was spoken here for probably two thousand years and which finally did out only in the present [20th] century. The list is not the result of any exhaustive survey but has been randomly compiled by me over a long number of years from the speech of my parents and of other residents of the locality, some still living, many now dead. I suspect that many such words have escaped my notice, while others which I have listed may now have disappeared. A few of the words are earthy and rarely heard in polite speech, but let the gentle reader not be ashamed of them, for they have a long pedigree. Close variants of them are to be found in Latin and Greek, in languages across Europe, and even in far-off India where they were brought in ancient times by our common Indo-European ancestors.

[Each English dialectal word is followed by the Irish word is is supposed to have derived from in brackets, followed by the meaning of the English dialectal word.]

Amadan (amadán), a fool.

Baakan (bacán), a timber roof-beam.

Bockan barra (bocán beara), a toadstool or mushroom.

Bardrucks (pardóg or bardóg) wickerwork creels slung across a donkey's back and used mainly for carrying turf.

Bing (beinn, binn), a large pile of potatoes etc.

Blether (bladar), nonsensical, boring talk.

Bothy (both), a small run-down house or shed, also found in Scots dialect.

Bresh (breis), a bout of illness.

Broughan (brachán) porridge.

Bruteen (brúitín) mashed potatoes with butter, the Irish version of poundies.

Brock (broc), a badger, also in Scots.

Budyin (boidín) a penis, sometimes used as a term of abuse

Brose (broghais), a fat, unwieldy person.

Brew (bruach), the edge of a river or turf-bank.

Bussock (basóg), a blow with the open hand.

Cack (cac), human excrement.

Calderer (cealdrach), a foolish person.

Capper (ceapaire), a slice of bread and jam.

Car (cár), a grimace, a cross face.

Clabber (clabar), mud or muck.

Crag (crag), a handful.

Craw (cró), outhouse for pigs, etc.

Crig (Criog), a rap, a blow.

Diddy (dide), a woman's breast.

Deelog (daolog), any kind of beetle or cockroach.

Drig (driog), a small drop, the final drop of milk from a cow.

Dreedar (dríodar) sediment in the bottom of a bucket of water.

Dull (dol), a wire loop used as a rabbit snare.

Guggy (gogaí) a childish name for an egg.

Gub (gob), the mouth.

Gorreen (goirín), a pimple or boil.

Gammy (gámaí), a fool, a stupid person.

Glar (glár) green scum on a well or stagnant pool.

Gowpen (gabhpán), the full of two hands held together.

Gra (grá) love, liking "I have no gra for that fellow".

Gulpen (guilpín) an ignorant lout.

Greeshey (gríosach), hot embers.

Jore (deor), a small drop of any liquid.

Keeney (caoineadh), wailing or howling, often said of a dog.

Kesh (ceis), heather, rushes, etc. placed so as to allow passage over a boggy place.

Kippen (cipín), a small stick.

Kitthog, kitter (ciotach), left-handed.

Lafter (lachtar), a brood of chicks or young turkeys

Looder (liúdar), a heavy, hard blow.

Loughryman (luchramán), a leprechuan, an elf.

Lug (log), the ear.

Lubber (liobar), a hanging lip, or a person with such.

Markin (mairtín), an old sock with the sole missing.

Miskin (meascán),a lump of home-churned butter.

Mullan (mullán), a small, round hill.

Malken (mulcán), a soggy mass, e.g. overboiled potatoes.

Pittick (piteog), a small, effeminate man.

Poreen (póirín), a small potato.

Puth, puss (pus), a sour face.

Scobe (scuab), a shallow bite from an apple or vegetable.

Scregh (scréach), a shriek, a screech.

Shall-fasky (seal foscaidh), a rough shelter, a calf-shed.

Shebeen (síbín), an illegal tavern.

Sheebowing (siabadh), drifting snow.

Sheeg (sidheog, síog), an elongated 'hip-roofed' haystack.

Slig (sliog), an old cutaway boot.

Sowans (Samhain) Oaten gruel formerly eaten from Hallowe'en onwards through the winter.

Spag (spag), a big foot.

Spiddick (spideog), abusive term for a small person.

Spink (spinnc), a steep, rocky slope.

Splank (splanc), a spark from the fire.

Tubashtey (tubaiste), an accident, a disaster.

Friday, December 26, 2014

Thursday, November 27, 2014

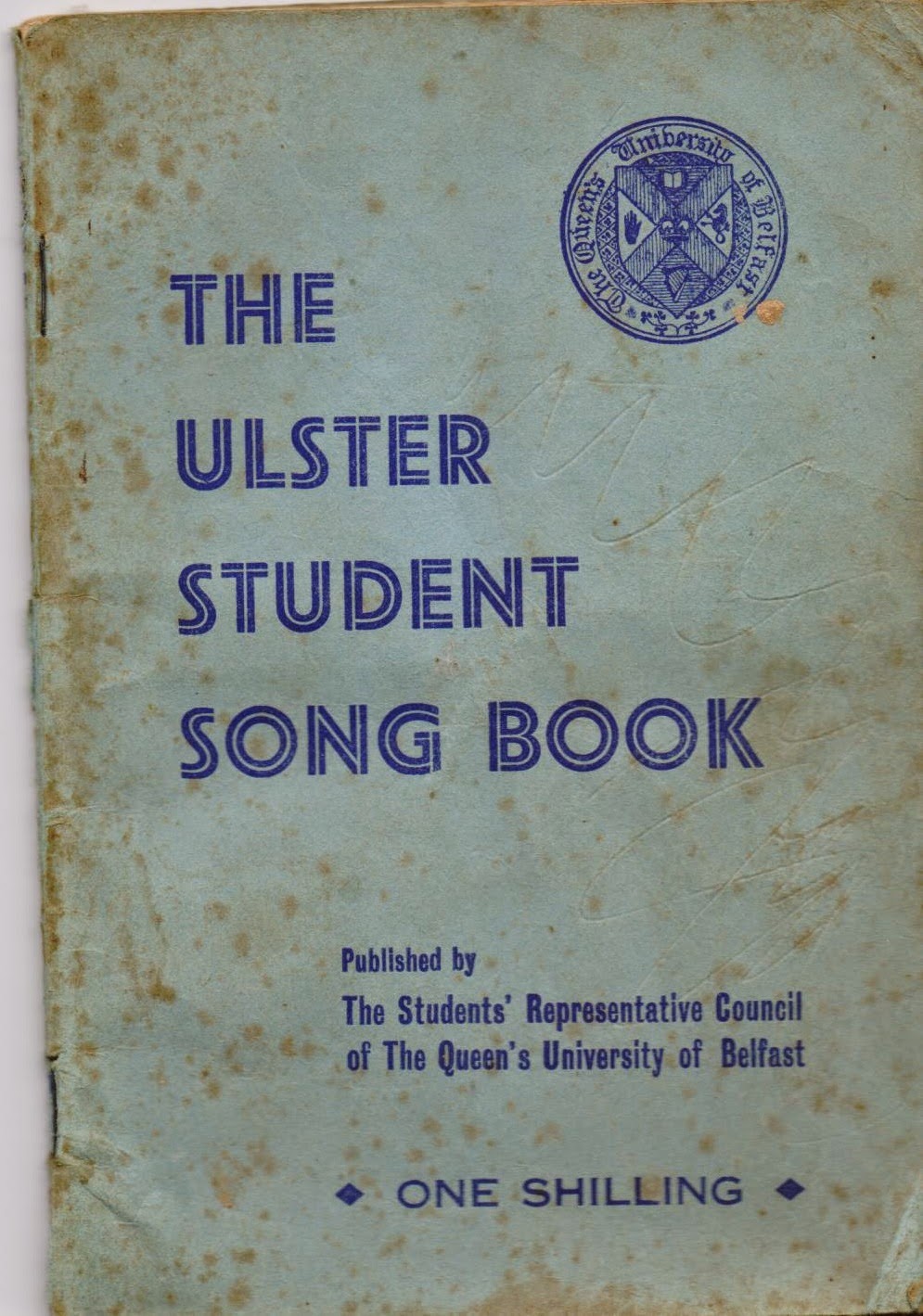

The Ulster Student Song Book (1957)

Here's another gem from my late father's vast store of curios. It seems it was published in 1957. The booklet contains songs mainly from the Irish tradition but also includes student staples of the day and appears to have seen a lot of use. The booklet contains advertisements for various Belfast companies which I've included below. I don't know if any of these firms still operate but if they do I'd be happy to hear about them.

To my mind the most historically fascinating section of the book is "Songs To Stir The Blood". Herein is published the lyrics to songs such as The Minstrel Boy, A Nation Once Again, The Wearing Of The Green, and Kelly, The Boy From Killane. These are songs which remains staples of republican balladry to this day. The songs are published alongside "The Ould Orange Flute", "The Sash My Father Wore", and other perennials from the loyalist tradition.

Queen's University of Belfast has been, from the outset, a non-sectarian centre of learning. In 1957, when the book was published, approximately 20% of its students came from a Roman Catholic background. This percentage would increase throughout the rest of the 20th century and beyond. I find it fascinating that it was permissible to include the republican ballads at the time given that in 1954 the Flags and Emblems (Display) Act (Northern Ireland) essentially forbid the flying of the Irish Tricolour in the six counties. Similarly the IRA's Border Campaign was ongoing at the time of publication.

The Education Act of 1947 brought in free secondary level education in Northern Ireland (as well as the rest of the UK) and student grants were also provided for in the act. This meant that children from less well off families were for the first time able to avail of third level education. Roman Catholic participation in third level education skyrocketed thereafter.

Thursday, November 20, 2014

Happy Christmas? (1971)

I must first apologise for the long hiatus, I was busy with other stuff including putting together a book which I shall plug ad nauseum at some point in the future.

This Christmas card-styled pamphlet fell out of a book in my dad's collection a few years ago. Alas, he had already flitted off to another realm so I didn't get a chance to ask him how he came about acquiring it. It is from 1971 and was published by People's Democracy as a protest against internment in Northern Ireland. Internment had been introduced as part of Operation Demetrius which saw 100s of mainly Catholic/Nationalist civilians arrested and detained without trial. This activity was legally justified by provisions of the Special Powers Act (NI) as described. Long Kesh is where the internees were imprisoned. The Nazi figure is Brian Faulkner, then Prime Minister of Northern Ireland. Faulkner was the last Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, serving from March 1971 until March 1972, and had presided over Operation Demetrius' implementation.

This Christmas card-styled pamphlet fell out of a book in my dad's collection a few years ago. Alas, he had already flitted off to another realm so I didn't get a chance to ask him how he came about acquiring it. It is from 1971 and was published by People's Democracy as a protest against internment in Northern Ireland. Internment had been introduced as part of Operation Demetrius which saw 100s of mainly Catholic/Nationalist civilians arrested and detained without trial. This activity was legally justified by provisions of the Special Powers Act (NI) as described. Long Kesh is where the internees were imprisoned. The Nazi figure is Brian Faulkner, then Prime Minister of Northern Ireland. Faulkner was the last Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, serving from March 1971 until March 1972, and had presided over Operation Demetrius' implementation.

Friday, July 11, 2014

Old And New Claddagh (1931)

Young lady of the Claddagh, 1931 (Corbis/Sexton)

The Claddagh, 1931 (Galway Advertiser/Sexton)

These are some of my favourite photos taken in Ireland for a number of reasons. First off, they beautifully and poignantly encapsulate the huge change the small community of the Claddagh was undergoing at the time. The people of the Claddagh had differed in custom and culture from other city dwellers just a short distance away and its array of thatched cottages seemed a relic of a bygone, more primitive era long before the 1930s. The fishing village's old world charm and unique customs attracted all manner of artists, photographers, and writers during the 19th and early 20th century.

The Claddagh, c1901 (Corbis)

The older houses, though picturesque, especially to tourists who typically had nicer abodes to go home to, were deemed unsuitable for modern living and were replaced with more comfortable but nondescript suburban housing which stands to this day. From a cursory search of contemporary newspapers it seems there was some local opposition to the rebuilding of the village. Some commented that the rents on the new dwellings was too high, others complained that if some work had been put into providing proper sanitation that the older cottages (some of which no rent was charged on) would be fine. Others still, with an eye on posterity and tourist dollars, marks, francs and pounds, suggested that at least a few of the finer examples of cottages should have been preserved.

Cartoon from Dublin Opinion, early 1960s

Beyond what these images specifically represent it is interesting to consider them in terms of broader societal changes in the wake of the creation of the Irish Free State. The 1920s had seen the establishment of 2RN, that national radio broadcaster, the construction of the ambitious Shannon Scheme, and the early 1930s would see the establishment of the first national commercial airline, Iona National Airways. As well as these technological and infrastructural changes, Ireland was continuing its long march from becoming a predominantly rural nation to becoming a largely urban and suburban one through a combination of migration to the towns and cities and the long blight of emigration. Although the Claddagh was not a rural village, part of its uniqueness was its existence in the midst of a modern city, it had a rural character that was all but totally erased by its redevelopment.

The powers that be in the Free State were often ambivalent about the march of social progress (see the 1930s anti-Jazz hysteria or the Mother and Child Scheme debacle of the 1950s for just two examples) yet at the same time, especially as regards Ireland's built history they could be callously proactive in replacing older structures. Having not been a resident of the Claddagh at the time I can't say for definite the village should or shouldn't have been so drastically rebuilt but it seems to me that maybe some compromise, as suggested at the time, might have been preferable. Contemporary accounts suggest that similar schemes in Dublin and other cities that created superior suburban housing for former tenement dwellers were also sometimes looked on in two minds, with many feeling a sense of dislocation from their former communities, despite obvious material improvements in their living conditions.

Workman demolishing cottage in The Claddagh, 1930 or 1931 (Corbis). Note the cottage directly behind is still occupied.

Renewal is of course always an issue, with successive governments facing damned if they do, damned if they don't criticism when they act to replace older dwellings and other structures. Tradition, history, heritage, are all also luxuries of those who already live in unquestioned modern comfort. Finally, perhaps what makes these images most resonate with the modern Irish viewer is how reminiscent the scenes are of the half-finished ghost estates that dot the Irish landscape at the present time, the result of bad planning, irrational exuberance, and systemic corruption. The Claddagh images contain the ghosts of the past, the image below, the ghosts of the future.

Ghost estate near Loughrea, Co. Galway, 2013 (Rolf Haid/Corbis)

Thursday, July 10, 2014

Dublin 1980: The Glue Sniffers

This article written by Gene Kerrigan with photos by Andrew McGlynn originally appeared in the September 1980 issue of Magill Magazine.

Wednesday, July 2, 2014

From Contemporary Ireland (1908) by L. Paul-DuBois

Below is an excerpt from L. Paul-Dubois' "Contemporary Ireland" from 1908 which provides a vivid (and to my mind touching) tableau showing some of the effects of the Gaelic Revival. It's also interesting in that it clearly indicates that adult education, nowadays ubiquitous, was at the time quite a novel concept. "Contemporary Ireland" can be found in its entirety here.

But the stranger is most forcibly struck when he attends some Irish class in a poor quarter in Dublin, or even London, and perceives how serious, deep, and infectious is the enthusiasm of the crowd, young and old, clerks and artisans for the most part - with an "intellectual" here and there - who are gathered together in the ill-lit hall. To these there is no doubt the thought of learning anything, and above all of learning a language other than English, would never have occurred at any other time, but now after their day's work, they sit here with an O'Growney* in their hands, with shining eyes, and strained looks, greedily listening to the lesson, following with their lips, con amore, the soft speech of their teacher.

The English which they speak with a remarkable native accent is, as has often been remarked, an English learnt from books, and full of absurd Irishisms which have remained locked up within their brains, a heritage of which they were not aware; it is an English built artifically upon a Gaelic substructure.

*Eugene O'Growney was a priest and Irish scholar who wrote the then popular textbook "Simple Lessons In Irish".

But the stranger is most forcibly struck when he attends some Irish class in a poor quarter in Dublin, or even London, and perceives how serious, deep, and infectious is the enthusiasm of the crowd, young and old, clerks and artisans for the most part - with an "intellectual" here and there - who are gathered together in the ill-lit hall. To these there is no doubt the thought of learning anything, and above all of learning a language other than English, would never have occurred at any other time, but now after their day's work, they sit here with an O'Growney* in their hands, with shining eyes, and strained looks, greedily listening to the lesson, following with their lips, con amore, the soft speech of their teacher.

O'Growney's "Simple Lessons In Irish"

Evidently here are people who have been transformed to the core of their being by this somewhat severe study, and by the importance of the social role which they wish to play, and which in fact they do play. Here, as elsewhere, the Gaelic movement has given an object, a goal, an ideal, to lives which, from their conditions, are often empty in these respects. Those who are in a position to know say indeed that few people of national feeling have taken up the study of Irish without being quickly aware of its strengthening and stimulating influence, without being fascinated by it as by a revelation. This shows that the language is for the children of Erin neither a dead language nor a strange one, but an integral part of their nature, a second self, an element of themselves that they had forgotten.

The English which they speak with a remarkable native accent is, as has often been remarked, an English learnt from books, and full of absurd Irishisms which have remained locked up within their brains, a heritage of which they were not aware; it is an English built artifically upon a Gaelic substructure.

*Eugene O'Growney was a priest and Irish scholar who wrote the then popular textbook "Simple Lessons In Irish".

Friday, May 30, 2014

Johnny Forty Coats (1943)

"Forty Coats, how many coats ye wearin' today?" - Forty Coats chatting to a young lad in Dublin, February, 1943 (Independent Newspapers)

Most Irish people of a certain age have heard the name Forty Coats. Those familiar with the name will probably recall the popular children's TV character on RTÉ in Ireland in the 1980s. What you may not realise is that the character was loosely based on a real person, PJ Marlow. Marlow, and perhaps other vagrants in Dublin in the 1930s and '40s, was known by the name Johnny Forty Coats or Forty Coats.

RTÉ's popular Fortycoats (http://labhaoisenidhuibhir.blogspot.ie/2012/10/born-in-80s.html)

Johnny Forty Coats was a Dublin vagrant who was so named for his habit of wearing multiple overcoats regardless of the weather. Francis Mc Manus, writing in an obituary for him in the Irish Press in February, 1943 described him thus, "Winter or Summer, he dressed as if he were living in some blizzard-stricken spot within a stone's throw of the Arctic Circle. He wore innumerable overcoats - perhaps he himself forgot how many of them there were! - until he was encased and layered like a fine onion."

Another snap of Forty Coats from February, 1943 (Independent Newspapers)

Forty Coats cut an odd figure traipsing the streets of 1930s and 1940s Dublin but he was well regarded and well recalled. Apart from his gentle eccentricity, his only apparent vice was his habit of spitting on the floor of the cafés that would allow him be a patron. He seems to have been particularly popular with the children in the neighbourhoods he wandered. McManus, again writing in that 1943 obituary,

I take it that "dekko" means a look at but it's not a term I've come across before. Pete St. John, writer of such perennials as The Fields Of Athenry and Dublin In The Rare Old Times, referred to Johnny Forty Coats in the chorus of his song about the Dublin of his youth, The Mero. The song also references Bang Bang, another still fondly remembered Dublin street character.

And we all went up to the Mero,

hey there! Who's your man?

It's only Johnny '40 coats',

sure he's a desperate man.

Bang Bang shoots the buses

with his golden key.

Hey! Hi! Diddeleedai,

and out goes she.

Forty Coats gets several mentions in the papers in 1943 and it appears that he passed away sometime that year. However, despite the appearance of an obituary for him it isn't at all clear to me that he did indeed shuffle off then. For example, having published an obituary for him the Irish Press ran a short story, a retraction of sorts, headlined "Forty Coats Is Still Going Strong" later in February, 1943, which includes some extra biographical information on the man.

Mentions of Forty Coats trail off in 1943 but his name appears in passing in articles in 1944 and 1946. If anyone has further information on the man please leave a comment.

Johnny Forty Coats, sans hat, 1943 (Independent Newspapers)

Monday, May 12, 2014

Old Borough National School, Swords, Co. Dublin (1809)

Visitors to Swords brave enough to venture beyond the palatial confines of the Pavilions Shopping Centre may have noticed the Old Boro Pub, a rather imposing building that sits at the junction of the Malahide Road and the nowadays rather forlorn looking Main Street. Its size makes it look more like a hotel than a simple public house. The building operated as a primary school for 191 years until closing in the year 2000. A new school was built around the corner and the Smith Group took on the old school and converted it into the popular watering hole it now is.

The Old Boro Pub in recent times (Source: Geograph.org.uk)

The town has its fair share of notable buildings, including the Round Tower and Clock Tower of St. Columba's and the 800 year old Swords Castle, all of which are mentioned in a previous post of mine. However the school building is by far the most significant one constructed in the town during the 19th Century.

The Old Borough School as depicted on a postcard circa 1900

As the 19th Century commenced Swords was a small village mainly populated by farm labourers. It would be many years before its character would be irrevocably altered by the construction of Dublin Airport at Collinstown, a couple of miles to the south, and the rapid suburbanisation and industrial development of the town it spurred. While the town was not of any great importance throughout much of its history by some quirk of politics it was allowed elect two MPs to the Irish Parliament. Weston St. John Joyce had this to say of the political arrangement:

"Swords was constituted a borough by James I, returning two members to the Irish House of Commons, and was one of the few free boroughs in Ireland (ie, not private property), the franchise having been vested in what were called, in the slang of the period, "Potwallopers", meaning Protestants who had been resident for a continuous period of six months."

With the Acts Of Union of 1800 and the consequent dissolution of the Irish Parliament, Swords was granted a juicy compensation package for foregoing its political clout. The princely sum of £15,000 was awarded to the town. Local grandees decided that the entirety of this money would be spent on a school or schools in the locality.

The Old Boro National School as it was in the 1970s looking pretty much the same as it had for the previous 160 years. (Source: South Dublin Libraries/ Patrick Healy Collection)

The construction of the school was a big deal as save for Swords House and the vicarage on Church Road, there had been no significant buildings erected in the town since Norman times. By all accounts the construction caused a mini-boom in the hitherto economically depressed town, as it took a lot of labour to bring the project to fruition. The design of the school building was tasked to Francis Johnston, better recalled these days as the architect responsible for Townley Hall in Louth, Dublin's storied GPO and St. George's Church on Hardwicke Place, also in Dublin. It seems his initial designs were rather extravagant and it was only on the fourth revision that his more frugally minded design was given the go ahead. Consequently, the structure has none of the finesse of many of his other works but is still to my mind a handsome building.

One of Francis Johnston's plans of the Old Borough School (Source: Áine Shields)

In my younger days I wondered why the handful of Protestants of primary school age in the town got this seemingly enormous building to themselves while the Catholics and everyone else attended drab utilitarian looking 1970/80s built schools with plenty of prefabricated additions. Initially the school was integrated, taking children in of school age, regardless of denomination, and due to the endowment, no fees had to be paid by any of the childrens' parents. There were other perks to attending the school, such as free coal and funding for several apprenticeships every year.

While the student body was integrated the ethos of the school was Church Of Ireland. This didn't sit well with the Catholics of the town, who lobbied for years to have the issue redressed. Catholic primary schools were established in the town's former chapel in the 1830s although they were fee paying and it wasn't until 1853 that the last Catholic students ceased attending the Old Borough school. In 1855, a dedicated Catholic primary school was built on Seatown Road in the town.

Although the issue of ethos and curriculum was addressed by having separate denominational schools there still remained the issue of funding. The administrators of the Old Boro School still controlled the purse strings of the endowment. The provision of funding would remain a contentious issue for years to come, which wasn't fully resolved until 1887 when an equitable division of endowment funds between the Protestant and Catholic schools was agreed under the provisions of the Educational Endowment (Ireland) Act, 1885.

While the student body was integrated the ethos of the school was Church Of Ireland. This didn't sit well with the Catholics of the town, who lobbied for years to have the issue redressed. Catholic primary schools were established in the town's former chapel in the 1830s although they were fee paying and it wasn't until 1853 that the last Catholic students ceased attending the Old Borough school. In 1855, a dedicated Catholic primary school was built on Seatown Road in the town.

Catholic School, Seatown Road, built 1855, obscured by a horrendously misjudged Celtic Tiger-era addition. (Source: http://www.andreworourke.ie/)

Although the issue of ethos and curriculum was addressed by having separate denominational schools there still remained the issue of funding. The administrators of the Old Boro School still controlled the purse strings of the endowment. The provision of funding would remain a contentious issue for years to come, which wasn't fully resolved until 1887 when an equitable division of endowment funds between the Protestant and Catholic schools was agreed under the provisions of the Educational Endowment (Ireland) Act, 1885.

Tuesday, April 29, 2014

Historical Ireland (1957)

My favourite illustration is the one from the Easter Rebellion. The sparring cop and other gentlemen look more like they're illustrating the Dublin Lockout of 1913. I'm not sure if this is a mistake or simply artistic licence. There's a lot of charm in the map, despite inaccuracies, and it's always interesting to see a map in a non-standard format like this, Ireland is almost at a right angle relative to how it is typically depicted.

Wednesday, April 16, 2014

Nelson's Pillar (1963) And What's To Be Done With History?

(The Pillar, 1963, Dublin Corporation)

(The Pillar, 1966, Archiseek)

(King Billy, College Green, c1900, Streets Broad And Narrow)

As part of more official erasure of monuments there was the removal in 1947 of a statue of Queen Victoria, which had stood in the grounds of Leinster House from 1904. That statue had an afterlife of its own detailed over at Come Here To Me.

(Queen Victoria Statue being removed from Leinster Lawn, 1948, Come Here To Me)

(Cartoon lampooning the removal, published in Dublin Opinion Magazine, August, 1948)

The debate on decolonisation has also extended to the wider built environment with buildings dating to the colonial era often in jeopardy. Few may ever lament the concrete piles the Soviets littered across the map of Central and Eastern Europe but much of Dublin's Georgian heritage was either wilfully levelled or let fall to rack and ruin, partly out of a sense that these buildings represented Ireland's former colonial masters and should be erased. All of this is part of a never-ending public debate about what stories should be recalled and what should be forgotten and I suppose there is no clear right answer. A complete blotting out of our (currently) undesirable pasts would be impossible and probably a huge disservice to human civilisation if it were feasible, but then not everything can or should be preserved. Time marches on, social needs and priorities change.

In the wake of World War II, the Allied Control Commission in Germany ordered the complete destruction of all buildings and memorials linked to the Nazis. At that point in time however, most of Germany lay in ruins and intact buildings were scarce. Hence, despite the order, much of the architecture of the Nazis remained. It was expedient to remove swastikas and other overt Nazi regalia but to leave the buildings intact. A later generation of Germans have debated whether these buildings should be preserved. A similar debate has ensued with regard to the restoration of buildings constructed during Mussolini's reign. It has been pointed out that much of Italy's most prized older built heritage was also undertaken beneath the foot of tyrants.

*The attack on the Gough statue inspired a hilariously crude poem, Gough's Statue, by Vinnie Caprani. Below is the second verse.

"’Neath the horse’s big prick a dynamite stick

some gallant ‘hayro’ did place,

For the cause of our land, with a match in his hand

Bravely the foe he did face;

Then without showing fear – and standing well clear-

He expected to blow up the pair

But he nearly went crackers, all he got was the knackers

And he made the poor stallion a mare!"

Monday, February 17, 2014

What does graffiti tell you about a place and a time? (Belfast, Derry City, Armagh City, 1970s)

While collecting images for my Old Ireland Pictures Twitter account I came across these images of graffiti in various cities in Northern Ireland. They all date from the 1970s, two from predominantly Protestant, Unionist areas and two from predominantly Catholic, Republican districts*. Graffiti has probably existed since people have been able to write and there are numerous examples of ancient graffiti to be found in Egypt, Rome, Greece, and the like. One of the slightly dubious delights at sites such as New Grange is seeing 19th century and older graffiti inside it. Like the marginalia found in illuminated manuscripts graffiti can lend the historian a different, less formal insight into a time and a place than the official narrative.

The examples of graffiti I've included can I suppose be seen as an ancestor of sorts to the political murals that I've written about before. The first image above, which shows graffiti that espouses a quite clearly Unionist perspective, includes "Keep Ulster Protestant", "God Bless Paisley", "God Save The Queen", and "O'Neill The Lundy". While the first three are probably self explanatory, the Paisley being of course Ian Paisley, the Queen being Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the last one might need a bit of explanation. The O'Neill referred to was Captain Terrence O'Neill, who was Prime Minister of Northern Ireland between 1963 and 1969. O'Neill felt it expedient to achieve a rapprochement with, and bring in reforms to improve the lot of, Northern Irish Catholics. In the eyes of many Northern Irish Protestants this was tantamount to treason. A Lundy is any traitor to the Protestant Unionist cause. The term, especially well known in Derry City and environs, refers to Robert Lundy, Governor of Derry during the Siege Of Derry. Due to either treachery or perhaps rank incompetence, Lundy seemed to do all in his power to let King James II's forces take the city. To this day he is burned in effigy.

Geoffrey Street, near Crumlin Road, Belfast, 1973

The Bogside, Derry City, 1972.

The graffiti in this next image comprises the slogan "Easter 1916-72", an Irish tricolour, and "Provisionals For Freedom". The first slogan obviously commemorates the 1916 Rising although I'm not sure why 72 was included. The latter, sounding almost like an advertising slogan, espouses support for the Provisional IRA. In the background is the Walker Monument which was blown up by the aforementioned Provisional IRA in 1973. All that remains of it in public view is the plinth.

Belfast, 1970s, I am not sure of the locale.

The presence of a Vanguard Unionist graffito indicates this photo was probably taken in 1972 or shortly thereafter. The three most prominent slogans are "Paisley For P.M.", "UVF", and "We Are The People". The first slogan is somewhat prescient with Ian Paisley having served as First Minister of Northern Ireland over 30 years later. The second stands for the Ulster Volunteer Force, a Protestant Loyalist paramilitary group. The last one had me perplexed for a minute as I had only ever heard "We Are The People" in the song Free The People by the Dubliners, an anti-internment ballad. However, it seems in this context it is a popular Glasgow Rangers slogan, a team associated with Northern Irish Protestant culture.

Armagh City, again I don't know what street/area this is, early 1970s.

This last example of graffiti in Northern Ireland features a grocer's apostrophe. First there's "Pig's Out", an anti-police sentiment voiced by many people in many different places over the years, but clearly understandable in the context of Catholic Republican animosity as regards the then RUC. The second part is calling for a "Worker's Republic" which is a term most associated with James Connolly. Many Irish Republican groups called for a 32-county Workers' Republic to be formed, that is not only an independent Ireland, free of British rule, but also organised on socialist principles.

All of the above examples display touchstones of the sociopolitical culture of their respective communities. One thing they all have in common is they're very basic. That is, white paint and a simple font is used in each example. A simple Irish Tricolour in the second example is the only graphic to be seen. In this sense these examples of graffiti diverge greatly from later luridly coloured political murals and indeed modern day graffiti which is often colourful and sophisticated in a visual sense.

*I am fully aware that there are Republicans who aren't Catholic and that there are Unionists who aren't Protestant but for the sake of brevity I have used Catholic Republican and Protestant Unionist.

Friday, January 10, 2014

Ré Nua (1990)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)